Genocide Watch exists to predict, prevent, stop, and punish genocide and other forms of mass murder. Our purpose is to build an international movement to prevent and stop genocide.

Staff Login

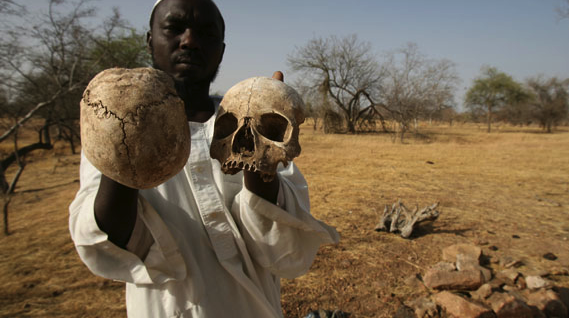

Darfur: What is left

Reckoning the Costs: How many have died during Khartoum’s genocidal counter-insurgency in Darfur? What has been left in the wake of this campaign?

Eric Reeves

18 March 2016

There is a growing possibility that the National Islamic Front/National Congress Party (NIF/NCP) regime in Khartoum will soon prevail militarily in its thirteen-year campaign in Darfur. The current Jebel Marra offensive seems increasingly likely to overwhelm the last resistance by the Sudan Liberation Army/Abdel Wahid, and thus the last major natural redoubt controlled by rebel forces in the region. If in fact Khartoum prevails, we may sure that military resources (including Antonov “bombers”) now utilized in Darfur will be moved to the ominously growing campaign in South Kordofan. It does not appear premature to begin something like a retrospective account of the immense cost of the genocidal counter-insurgency that began in 2003.

The UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, in its March 15, 2016 “Sudan Humanitarian Bulletin,” reports figures revealing that the number of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) is greater than at any time during the thirteen years of violence and civilian destruction in Darfur that have defined Khartoum’s pursuit of a genocidal counter-insurgency. 2.66 million people were displaced as of December 2015; 110,000 people have fled to North Darfur and South Darfur during the current Jebel Marra offensive. There are no definitive figures for Central Darfur and Jebel Marra itself; but estimates from the UN and other sources suggest that the number is again measured in the tens of thousands. In short, some 2.8 million are internally displaced in Darfur, overwhelmingly from the non-Arab/African tribal groups of the region.

The UN High Commission for Refugees in its “2015 Country Operations Profile—Chad” reports that approximately 380,000 Darfuris were refugees in eastern Chad. Although this figure has been reduced by some 60,000 refugees who have evidently returned to Um Dukhun in West Darfur and Tina and Karnoi in North Darfur, we cannot be sure of the cause of these returns. WFP budgeted nothing its food operations for the twelve camps along the Chad/Darfur border, and many have returned to Darfur not because of improved security but because they were slowly starving in Chad, where the regime of Idriss Déby has made clear its desire to remove the Darfuri refugee population. Still, more than 300,000 Darfuris remain in Chad as refugees living in increasingly tenuous circumstances.

We have no reliable census for the number of girls and women raped during these terrible thirteen years, but all evidence suggests that the figure is many, many tens of thousands (see my analysis of rape in Darfur for the years 2014 – 2015:

Continuing Mass Rape of Girls in Darfur: The most heinous crime generates no international outrage

| January 2016 |

Darfur suffers as well from the broad food shortage that is increasing throughout Sudan, with a population of million suffering from Acute Malnutrition. 4 million people are or will become seriously food insecure in 2016, and in some regions the situation is catastrophic. The South Kordofan/Blue Nile Coordinating Unit reports (March 2, 2016) that: “As many as sixty four percent (64%) of households in the [Kau-Nyaro-Warni area are severely food insecure; and a further thirty six percent (36%) are moderately food insecure (total 97%).”

Water shortages—for both livestock and people—are reported constantly throughout Darfur, but particularly in Darfur, where many IDP camps have dangerously low capacity.

Thousands of villages have been destroyed, either wholly in part. Much of the destruction has been confirmed by satellite photography. Radio Dabanga reports an estimate that in the past two months alone, during Khartoum’s military campaign in Jebel Marra, 150 villages have been destroyed to date, even as a renewal of the offensive seems imminent:

East Jebel Marra, during the past three fighting seasons, has seen more than 1,000 villages wholly or partially destroyed. See my extensive data collection and mapping for November 2014 – November 2015:

“Changing the Demography”: Violent Expropriation and Destruction of Farmlands in Darfur, November 2014 – November 2015″

MORTALITY IN DARFUR, 2003 – 2016

The consequences of this massive, ethnically-targeted onslaught are clearly overwhelming in scale. Even so, we have no definitive account of how many people have died as a direct or indirect result of violence. The latter population includes death during flight from violence, a huge total unto itself; children—even infants—finding themselves without families; inadequate humanitarian resources for the displaced; and what epidemiologist refer to grimly as “deferred mortality”: deaths that are not immediate but are simply delayed or made more likely by the direct or indirect consequences of violence.

In the early years of the genocide, by far the greatest cause of death was violence itself. Failure to recognize this basic fact thoroughly vitiates an otherwise valuable mortality assessment (January 2010) from the Center for the Epidemiology of Disaster (CRED, Belgium), which essentially excludes violent mortality for the period February 2003 to what if vaguely referred to as “early 2004.” Since this is perhaps the very most violent year in the Darfur genocide, such a bizarre shortcoming destroys the credibility of any estimate of total morality from violence (the CRED distortion of data is discussed at length in my August 2010 mortality study, below). At some point, however—perhaps in 2006—the greatest cause of death became, and has remained, malnutrition and disease among the populations violently displaced.

The last time the UN offered an assessment of mortality in Darfur was in April 2008—eight years ago. At the time, Sir John Holmes, head of UN humanitarian operations, offered a figure of “300,000.” That figure—eight years later—continues to be cited in the world’s appallingly inadequate reporting on the region. In August of 2010, using all extant data and surveying all relevant reports, I produced the analysis that appears below. It concluded that approximately 500,000 Darfuris had died as of that date, overwhelmingly from non-Arab/African tribal groups. Although I had frequently attempt at earlier stages in the genocide to quantify the death total, since 2010 Khartoum has made impossible the aggregation of new mortality data, and both the UN and nongovernmental humanitarian communities seem content with the failure to take account of the lives lost.

But as I argued in a recent email interview with Agence France-Presse (an excerpt was included in the final version of the dispatch), efforts to establish the number who have died during violent conflict is neither morbid nor gratuitous, for two primary reasons:

[1] If we know how many have died, we have the single greatest indicator of how many more are likely to die if conditions remain unchanged. This is why continuing use of the April 2008 estimate of “300,000” is so disturbing. Although levels of violence have varied over 13 years of conflict, violence certainly produced, directly and indirectly, massive new mortality since April 2008. Had the world taken seriously the UN estimate of 2008, we would in fact have a much better sense of current mortality. And yet AFP, Reuters, the NY Times, The Guardian, Bloomberg are all constrained by, and use, the UN figure of 300,000 that can’t possibly be right.

[2] The second reason mortality estimates are important: if we don’t make every effort possible to ascertain human mortality, we are implicitly devaluing the lives of those who died but whose deaths don’t figure in our assessment of an ongoing humanitarian emergency. This is as true in South Sudan as it is in Darfur, as well as South Kordofan and Blue Nile. If we give up on establishing mortality estimates, if we content ourselves with only the easily gathered and quantified data, we are in one way or another saying that the lives of those not so easily captured in such data don’t “really count.” But they do matter, whether we count them or not.

Building on the figure of 500,000 from August 2010, I conclude that approximately 600,000 people have now died in the Darfur genocide. In extending my 2010 figure I am able to use no single set of data, but rather a close analysis of all reporting by Radio Dabanga; figures for Severe Acute Malnutrition for children under five (among whom the mortality rate is over 50 percent for those not in a hospital or therapeutic feeding center); data and reports from all dispatches by Sudan Tribune; reports and data from UN OCHA that allow some inference about mortality; reports from confidential sources on the ground; and a wide range of reports of conditions in the IDP camps.

Again, there are no hard data sets to aggregate, there is no certainty to the conclusions I draw from a reading of all published (and unpublished) reports on conditions and mortality in Darfur. Yet given the data spreadsheet from “Changing the Demography”: Violent Expropriation and Destruction of Farmlands in Darfur, November 2014 – November 2015″, I have concluded that it is impossible that significantly fewer than 100,000 civilians have died in the five and a half years since my August 2010 analysis.

For comparative purposes only, I might note that the April 2008 UN figure of 300,000 yields an average annual mortality rate of about 60,000. Wholly, coincidentally, my August 2010 analysis (coming two and a half years later, but using much fuller sets of data) also yields an average annual mortality rate of about 60,000. By contrast, a figure of 100,000 dead over the past five and a half years yields an average annual morality rate of under 20,000. Given the high level of violence and violent displacement over the past four years, particularly in East Jebel Marra, there are many reasons to believe that this may significantly understate mortality.

600,000 dead

It has become a truism of genocide studies that no two genocides are the same. The destruction of perhaps 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus in Rwanda in spring/summer 1994 was—in stark contrast with Darfur—largely over in 100 days, although the terrible aftermath of that vast spasm of ethnic violence is with us still. And the vast Nazi campaign to destroy European Jewry during the Second World Wars has too often served as a distorting paradigm of what genocide must be. But the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide specifies acts that have all defined Khartoum’s ruthless counter-insurgency campaign in Darfur:

Article 2

In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

“In whole or in part…” There can be no denying that 600,000 dead—overwhelmingly from the non-Arab/African tribal populations of Darfur, who have clearly been targeted “as such”—is a very substantial “part” of the “group.”

Darfur has been, and continues to be, the site of genocide—the longest genocide in over a century—one the world simply got tired of.

Eric Reeves | March 18, 2016

All Rights Reserved to the writer.