Genocide Watch exists to predict, prevent, stop, and punish genocide and other forms of mass murder. Our purpose is to build an international movement to prevent and stop genocide.

Staff Login

Guatemala: GHRC Visits Political Prisoners in City Jail

GHRC Visits Political Prisoners in Guatemala City Jail

El Quetzal

Published by the Guatemala human RiGhts Commission/USA

HUMAN RIGHTS NEWS AND UPDATES WINTER 2015-2016

ISSUE #20

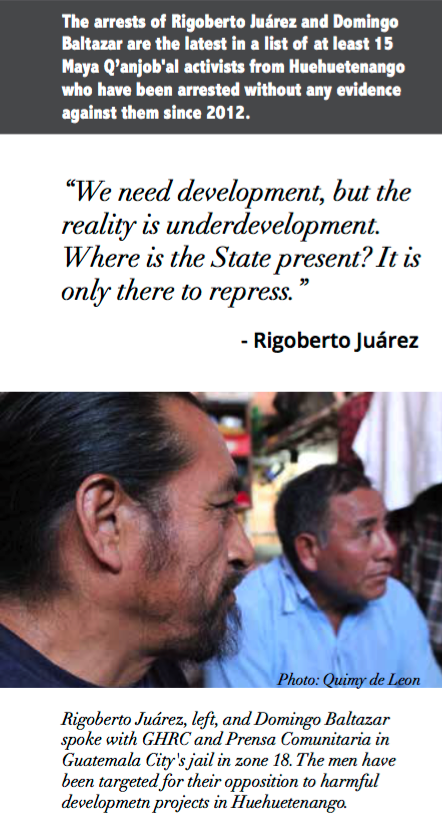

On August 14, 2015, GHRC and Prensa Comunitaria sat across from Rigoberto Juárez and Domingo Baltazar, two of many land rights defenders currently in Guatemala City’s jail facing trumped-up criminal charges in Guatemala. The visit represented an e ort to document conditions, take testimony, and provide moral support.

Although both Juarez and Baltazar were accused of “participating in the illegal detention of workers,” human rights organizations and observers believe their arrests to be a response to their e orts to defend indigenous rights and ancestral lands. Both are respected leaders in the Q’anjob’al community and were integral in the formation of the regional Plurinational Government in Northern Huehuetenango. They had been publicly involved in peaceful e orts to oppose transnational hydroelectric and logging projects in the region, as well as the e ort to reopen the Snuq’ JolomKonob’ community radio station in Santa Eulalia.

“There is great interest in appropriating the natural resources of our territory,” Juarez explained.

Juárez and Baltazar were arrested on March 24, 2015 as they walked down 6th avenue in Guatemala City, visiting the capital

to denounce abuses against themselves and their communities. Their defense lawyer, Ricardo Cajas, who contested the apparently warrantless arrest, says he was assaulted when he confronted police o cers on the issue.

Their detention follows an all-too-common pattern; over a dozen Maya Q’anjob’al activists from Huehuetenango have been arrested without probable cause since 2012. All have been targeted because of their political opposition to harmful development policies and

to speci c large-scale mining operations, hydroelectric dams

and other megaprojects. This criminalization occurs through an intentional abuse of the legal system in order to intimidate activists and quell dissent, and are often subject to arbitrary detentions, accused of serious criminal charges (including “terrorism”), and can spend months of pre-trial detention in inhumane conditions. Due to the lack of evidence corroborating the charges, the cases are typically dismissed – but the damage is done.

Guatemalan prosecutors have done little to address this pattern, in some cases they continue sham trials despite a lack of evidence, or rely solely on testimony of employees of the very companies that want to ensure their continued operations.

The cost to these political prisoners and their families is exceedingly high. Time spent in jail takes a tremendous physical and emotional toll on both defenders and their families, and even after being released, many continue to su er secondary consequences. They su er nancially due to legal fees and family travel expenses to visit the jail, and can encounter problems returning to work after their release.

Since their arrest, Juárez and Baltazar have remained incarcerated in Guatemala City. Their shared cell, a small room lled so full with bunk beds there is barely room to walk, is one of the safer areas of the jail. As in most Guatemalan jails and prisons, a heirarchy of inmates controls most of what goes on, and luckily in Sector 13, peoples’ basic needs are met.

Other concerns are often more pressing. The prison authority and police, for example, are responsible for transporting them to Santa Eulalia for each court date. They missed their rst hearing because no transportation was made available; they missed a second hearing set for July 17 because o cials picked them up at 6:00am for an 8:30am hearing. What is typically a 6-7 hour drive took far longer when the police made over a dozen stops along the way, not arriving until late at night. Having missed the hearing by a full day, they simply turned around and went back.

“We were made to ride in the back of a pickup with three others, under the sun and rain, without eating,

without being allowed to go to the bathroom,” the men told GHRC.

Despite expressing no urgent security concerns, Juárez and Baltazar spoke to GHRC in hushed voices, sometimes almost a whisper.

“We need development,” Juarez explained, “but the reality is underdevelopment. Where is the State present? It is only there to repress. Those of us who are opposed are considered insolent and poorly educated. We are listening to what our ancestors tell us, who have di erent rules and di erent ways of thinking. We put hope in God’s help, but also in the strength of many people.”

OTHER CASES: Saúl Méndez and Rogelio Velásquez were unjustly detained from May 2012 until January 2013. They were rearrested in August 2013, accused of complicity to murder, and in 2014 were sentenced to over 33 years in prison. The sentence was nally overturned on appeal; they were released in January 2016. Both were likely targeted due to opposition to Escoener Hydraulic Energy, a Spanish company that plans to build a series of hydroelectric dam projects in Huehuetenango.

In 2012, 11 people from Santa Cruz Barillas were detained under martial law, and spent between ve and eight months in jail on trumped-up charges before being released due to lack of evidence. They had been active in local opposition to another hydroelectric project, Hidro Santa Cruz, owned by a another Spanish company.

LA PUYA:

US Congress Calls on Guatemalan President to Halt Illegal Mining at La Puya

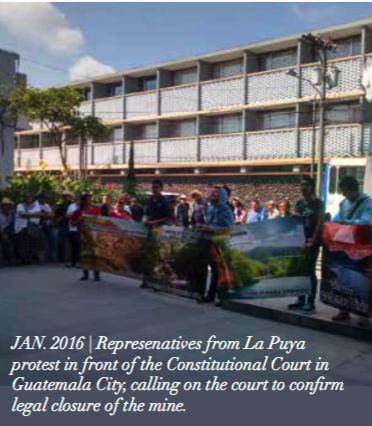

Opposition continues at La Puya four years after residents first physically blocked the entrance to a mining operation in their community – an ongoing act of non-violent resistance that has received global support. And in the last three months, residents’ arguments against the mine– legal, environmental and ethical – have been supported by the US Congress, the Municipal authorities, and Guatemalan courts.

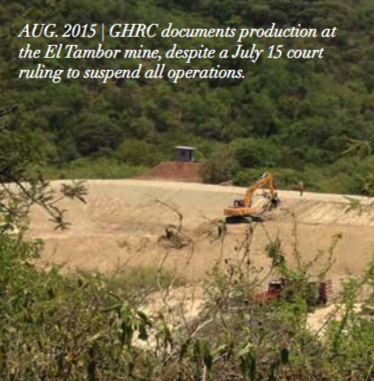

Yet the US-owned mine continues to operate.

On October 26, 2015, 12 Congressional members sent a letter to interim Guatemalan President Alejandro Maldonado Aguirre to raise concerns about abuses related to the El Tambor gold mine in San Pedro Ayampuc, Guatemala. Supported by GHRC, the letter calls on the President to use his authority to uphold human rights and to ensure that the mine’s owner–the US-based company Kappes, Cassiday & Associates (KCA)– promptly halts its illegal operations.

The letter responded to a Guatemalan court ruling on July 15, 2015, that found EXMINGUA, KCA’s subsidiary, has been operating the mine without valid municipal permits, did not consult with affected communities before the project began in accordance with Guatemalan and International law, and that the Environmental Impact Assessment was plagued with serious deficiencies. The court ordered an injunction against mining activities at El Tambor, a decision upheld after the company’s appeal.

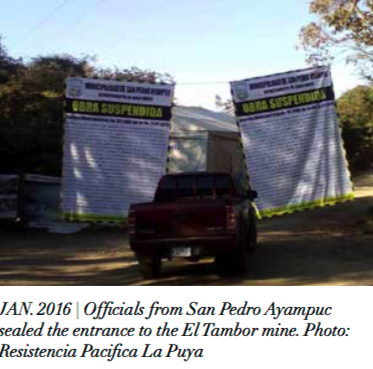

When mining continued, community members and their lawyers requested the municipal government grant temporary protection measures, which were approved. On Jan. 5, officials from the municipality of San Pedro Ayampuc, accompanied by police officers, arrived at La Puya to take suspend work at the mine. Officials sealed the entrance

to the project with tape and banners in order to enforce the measures. This, too, was ineffective; in the early morning hours of Jan. 6, company employees and riot police arrived at La Puya and removed the tape and banners, allowing machinery and workers back into the mine site. Community members are now calling on Guatemala’s highest court to confirm the municipal injunction that demands closure of the mine.

The ongoing illegal mining operation is just one of many abuses KCA’s mine has caused at La Puya. There has been no justice for Yolanda Oquelí, shot in 2012 when leaving the community blockade, nor has there been redress for the excessive use of force used by police in 2014 during the violent eviction to force access to the mine.

Activists have also faced trumped-up charges, and the US Congressional letter specifically called on the Guatemalan government to take active steps to release wrongfully imprisoned community leaders and initiate dialogue with residents to peacefully resolve the conflict.

GHRC ́s support continues for the peaceful opposition to the mine at the Puya. Staff meet frequently with community members and their lawyers, and in August spoke directly with municipal authorities. GHRC is also urging the US Embassy to take concrete steps to address the illegal activities of a US company.

Civil Society Petition Demands Justice for Killing of Activist, Ecocide in Petén

The Petén lowland rainforests of northern Guatemala have been beseiged for years by illegal logging, drug trafficking, cattle farming and oil exploration. Since the late 1990s, environmental damage in the region has been exacerbated by yet another phenomenon: a booming palm oil industry that has made Guatemala one of the world’s top producers. Encircled by these economic giants, human rights defenders continue to risk their lives to save their environment.

On Nov. 30, men and women from communities battling the destructive effects of palm oil production held before later denying involvement. At no point were community members warned of the spill, but it quickly became apparent that the water was poisoned. Later reports have estimated that at least 23 different species of fish and other aquatic life were found dead, affecting

the economic livelihood of at least 12,000 people from 17 communities. The incident has since been referred to as an “ecocide” by community members and experts alike.

Lorenzo Pérez, Hermelindo Asij and Manuel Pérez—were held by REPSA employees for almost 12 hours, threatened with being burned alive, before they were finally released.

During the Nov. 30 press conference, Juan Castro of the Association of Mayan Lawyers gave an account of a recent hearing on palm oil in Guatemala, held at the IACHR in Washington, DC. Activists also hoped that choosing Nov. 30, the date of the kickoff of the Climate Summit in Paris, would increase pressure on both domestic and international leaders to do more to protect communities defending their environment.

The violence surrounding the REPSA case is representative of a broader pattern of attacks against land rights activists, a phenomenon that many Guatemalan human rights groups consider to be linked to an unjust economic model that favors large companies over the a press conference in Guatemala City to deliver a civil society petition – signed by nearly 50,000 individuals– to Guatemala’s Attorney General Thelma Aldana. The petition, spearheaded by GHRC, ActionAid and Friends of the Earth, echoes local community demands for an immediate investigation into the contamination of the Pasión River as well as into the murder of environmental activist Rigoberto Lima Choc. Lima, a school teacher and indigenous leader, had been one of the first to report a mass die-off of fish along the river this past summer; on Sept. 18, he was shot dead by unknown assailants outside a local courthouse in Sayaxché, Petén. Community members first noticed a smaller die-off of fish in the Pasión River in April 2015, but it drew little national attention. Then, in early June, residents observed tens of thousands of dead fish floating on the river’s surface.

The contamination appeared to be directly linked to overflow from the processing plant of palm oil company Reforestadora Palma

de Petén S.A. (REPSA), which first timidly admitted responsibility

“We deplore these incidents,” said Lima in a June 17 press conference. “As community members, we are indignant. Truthfully, there are people who are unable to make a living – they depend on the river and they are being left penniless.”

Three months later, on September 17, REPSA was ordered to suspend its operations while an investigation into the source of the contamination is carried out. The next day, Rigoberto Lima Choc was assassinated in broad daylight.

Many media outlets have reported the likely connection between Lima’s assassination and his public demands to investigate REPSA’s alleged role in the contamination. In addition to his murder, three other human rights activists—rights and economic livelihoods of local communities.

“The prevailing model in Guatemala is known as accumulation by dispossession,” said Jorge Santos, a member of Guatemalan human rights group UDEFEGUA, in a recent interview with Telesur. “[It is] based on the commercialization of natural resources, mining extraction, hydroelectric projects to lower costs for industry, and monocultures, particularly sugar cane and African palm.”

GHRC, a coordinator of the joint petition, continues to support the case as communities seek justice for the death of Lima and the contamination of the river, which to date remains “under investigation.”

Activists Discuss Crackdown on Human Rights Defenders at IACHR Hearings

Though it was corruption that ultimately brought down former president Pérez Molina, the protests against him took place amid a broader crackdown on human-rights defenders of all stripes— including human-rights lawyers, journalists, labor activists, and indigenous groups resisting large-scale development projects.

This past October, members of Guatemala’s Human Rights Convergence and other civil-

society organizations participated in hearings at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and met with US government o cials to discuss these challenges.

In back-to-back hearings, petitioners highlighted the defamation and harassment of lawyers and expert witnesses in the ongoing genocide case against former Guatemalan leader Efrain Ríos Montt.

Pérez Molina, a former military general who vociferously denied that any genocide had taken place, was himself implicated in atrocities against indigenous Guatemalans in testimony that emerged during the trial.

In another hearing, lawyers and community leaders emphasized the precarious and vulnerable situation of communities surrounded by African Palm production, where residents su er harassment from palm-oil companies, contamination of their water supply, and other environmental problems.

On September 18, indigenous activist Rigoberto Lima Choc was assassinated outside a local courthouse in the northern town of Sayaxché, Petén. Lima was one of the rst to publicly denounce the actions of the palm company REPSA for its alleged involvement in the contamination of the La Pasión River.

Just weeks later, Alex Reynoso— an environmental activist who has organized against the Tahoe Resources silver mine in southern Guatemala—survived a second assassination attempt. An earlier attempt last year claimed the life of his daughter, 16-year-old Topacio Reyes.

Many human-rights organizations view these attacks as part of an ongoing pattern of repression against land-rights defenders, as well as a test for the

transitional government—one the administration has failed.

They accuse the government of dispatching security forces to protect transnational corporations—and suppress any resistance to corporate misconduct—while failing to properly respond to attacks against community leaders.

In a separate hearing on extractive industries, Commissioner Rose- Marie Antoine called the violence against indigenous activists resisting their own displacement a “total disgrace for democracies in the region.”

In all these cases, the Guatemalan government has categorically denied any responsibility or wrongdoing. “We’re sorry to see that the state maintains its same position,” said Center for Human Rights Legal Action Director Juan Francisco Soto, “even though we now have a new president, and new appointed officials in the country.”

Riding a wave of anti-establishment sentiment, Jimmy Morales—a comedian with no political experience and backed by military hard-liners—has been elected Guatemala’s next president.

Morales was inaugurated on Jan. 14 just days after he su ered an early political setback related to his Cabinet. On Jan. 6, one of his top advisers, Edgar Ovalle Maldonado, was among a group of ex-military leaders accused of crimes against humanity. For now, Ovalle cannot face prosecution due to his status as an incoming lawmaker, though Attorney General Thelma Aldana has has requested his immunity be lifted, and the appeals process has reached the Constitutional Court.

Morales saw his popularity surge amid a series of corruption scandals that led to mass citizen protests, the arrest of several high-level government o cials, and the resignation of former president Otto Pérez Molina this September. Capitalizing on his reputation as a political outsider, Morales achieved an unexpected rst-round win in September before defeating former rst lady Sandra Torres in the October 25 runo election.

Morales, like his opponent Sandra Torres, promised e orts to promote transparency and root out corruption. But he’s drawn criticism for his vague policies, his comedic reliance on racist, sexist, and homophobic tropes, and the fact that some of his backers—including the founders of his political party, the National Convergence Front (FCN)—are conservative members of the military linked to war crimes from the country’s three-decade armed conflict.

Though some Guatemalans are cautiously optimistic about the future, many remain skeptical that “The social movements we’re experiencing may mean that someday we’ll have different options— candidates who really represent the people.” – Iduvina Hernández

Morales will be able to pull the country out of its current political turmoil. “Nothing is going to change,” one voter said via Twitter— even as she cast her ballot.

In the past few months, many Guatemalans have lauded the transformative power of citizen protests, and some outlets called the country a leader in a new “anti-corruption spring.” But failed electoral reforms and ongoing land rights conflicts have prompted some to ask: Has anything really changed in Guatemala?

Responding to that question at a panel discussion in DC, Daniel Pascual from the Committee for Campesino Unity stated that civil society has been armed with new allies, and the country’s “social awakening” has given rise to a more informed and vigilant citizenry. With more people calling for justice, it will be ever more challenging for public officials not to act on behalf of the people.

Still, the vast majority of these urgent concerns—the ongoing militarization of public security, high rates of impunity, deep-rooted corruption, and increased violence against environmental activists, among a collapsing healthcare system and other issues—are issues President-elect Morales has barely mentioned. To date, he’s shared no plan or inclination to address them.

“Neither Morales nor Torres represent the change we need,” said Iduvina Hernández. “But the social movements we’re experiencing

may mean that someday we’ll have di erent options—candidates who really represent the people.”

HUMAN RIGHTS CASE UPDATES

18 Ex-Military Leaders Arrested for Crimes Against Humanity

Eighteen former military leaders — including former generals, a former army chief of sta , and a former military intelligence chief — were arrested on Jan. 6 on criminal charges related to massacres and disappearances from the internal armed con ict. Fourteen of the arrests pertain to an investigation on a military base known as CREOMPAZ in Cobán (formerly Military Base 21), where the remains of hundreds of people have been found and where the identities of at least 97 people have been con rmed as individuals disappeared during the 1980s, when the ex- o cials were in power. Four of the arrests relate to the disappearance of Marco Antonio Molina Theissen, a minor, in 1981. Twelve had trained at the US School of the Americas.

GHRC was one of the rst international groups to gain access to CREOMPAZ in 2012 to observe the exhumation, and advocated for families to have improved access. The CREOMPAZ facility, which continues to serve as a regional UN Peacekeeping training base, has received US funding.

The handling of these cases will be a test for president-elect Jimmy Morales, who will took o ce on Jan. 14. It was rumored that one or more of those facing charges had been tapped to participate in the Morales’ administration. One of Morales’ closest allies and the president of his party, Edgar Justino Ovalle Maldonado, is also a suspect but could not be arrested due to his immunity. Attorney General Thelma Aldana announced her o ce requested the Supreme Court to lift Ovalle’s immunity. The court denied the motion, but the decision has been appealed.

The cases also sparked controversy within the Defense Ministry when a high level o cial, acting, he said, in a personal capacity, led a motion to annul the Constitutional article that explicitly exempts gross violations from amnesty. The motion was denied and the General was relieved of his post.

The Sepur Zarco Case Goes to Court

More than 30 years after dozens of Q’eqchi women suffered sexual violence and sexual slavery at the Sepur Zarco military outpost, 15 women, with the support of the Alliance to End Silence and Impunity, will have their day in court. The women, now in their 70s and 80s,

are making history, as the trial opened Feb. 1. GHRC is present in the courtroom to observe the trial and will continue to send updates.

The Genocide Case Remains Stalled

After ongoing legal battles, the retrial in the genocide case scheduled for March 16. Rios Montt, found guilty of genocide and war crimes in the 2013 trial, was diagnosed in August with dementia. Any new trial will be a closed-door proceeding, though plaintiffs hope to separate the legal proceedings of Ríos Montt and co- defendant Rodriguez Sanchez so the latter could have a public trial. Victims and their lawyers, despite these delays, remain committed to achieving justice.

5 Comments

Lawfare against Maya authorities in Guatemala - Intercontinental Cry

Apr 28, 2016

[…] their freedom. They’ve received visits from Nobel laureates Rigoberta Menchú and Jodi Williams, human rights defenders, and three European Parliamentarians aware of Spanish capital involved in the hydro dam company […]

Guatemala's history of genocide hurts Mayan communities to this day - StuntFM 97.3

Jun 18, 2018

[…] land rights. Hundreds of other indigenous community leaders are being held without trial as political prisoners for their opposition to government and corporate activities. In 2015 a local human rights […]

Guatemala’s history of genocide hurts Mayan communities to this day

Jun 18, 2018

[…] land rights. Hundreds of other indigenous community leaders are being held without trial as political prisoners for their opposition to government and corporate activities. In 2015 a local human rights […]

Guatemala’s History of Genocide Hurts Mayan Communities to This Day - Latino USA

Jul 18, 2018

[…] land rights. Hundreds of other indigenous community leaders are being held without trial as political prisoners for their opposition to government and corporate activities. In 2015 a local human rights […]

Guatemala’s History of Genocide Hurts Mayan Communities to This Day

Jul 18, 2018

[…] land rights. Hundreds of other indigenous community leaders are being held without trial as political prisoners for their opposition to government and corporate activities. In 2015 a local human rights […]